What is Sukkot?

Sukkot, often referred to as ‘The Feast of Tabernacles,’ or ‘The Season of Rejoicing,’ is a seven-day festival beginning on the 15th day of the Hebrew calendar month of Tishrei. It is one of the most joyous Jewish holidays for many reasons, yet, perhaps made more so because it falls only five days after the end of Yom Kippur—the Day of Atonement—which is considered the most solemn and holiest day of the year.

Still, while Sukkot is a holiday of feasting and joy, it is not observed in a place many of us would consider ‘ideal.’ For it is largely spent in a sukkah—a temporary dwelling/booth, covered on top by plants (most often palm branches) in a way that not only allows the sun, moon, and stars to shine through, but also does not guarantee to keep rain, heat, or cold away. It is an environment many would not automatically rejoice in—particularly if the weather is inclement—yet, it is commanded by God in His Word and eagerly followed by His people.

“And you shall take for yourselves on the first day the fruit of beautiful trees, branches of palm trees, the boughs of leafy trees, and willows of the brook; and you shall rejoice before the Lord your God for seven days. You shall keep it as a feast to the Lord for seven days in the year. It shall be a statute forever in your generations… You shall dwell in booths for seven days. All… shall dwell in booths, that your generations may know that I made the children of Israel dwell in booths when I brought them out of the land of Egypt: I am the Lord your God.”—Leviticus 23:40-43

Why the Sukkah?

Sukkot is a week-long festival celebrating the ingathering harvest of the season and remembering God’s miraculous presence with the children of Israel when they left Egypt—but that is only the beginning.

Sukkot is celebrated in sukkahs, temporary dwellings covered with the branches of trees—a sign of God’s gifts from the earth in the season of ingathering. Yet, there is a deeper, holier reasoning behind its use…

It represents the years of wandering in the desert, when both the Jewish people, and the Tabernacle of God, had only temporary dwellings. It represents God setting His people free from the bonds of Egypt and keeping them safe and fed in the desert, even as they resided in sukkahs. It represents His Presence—His Glory—which hovered over the ‘Tabernacle of Meeting’ in a cloud by day and fire by night. It represents the Lord’s Presence and Glory leading the people of Israel with the sign of His cloud ascending from the Tabernacle to the place He would direct them. To their promised land.

Following the Cloud:

“Then the cloud covered the tabernacle of meeting, and the glory of the Lord filled the tabernacle. And Moses was not able to enter the tabernacle of meeting, because the cloud rested above it, and the glory of the Lord filled the tabernacle. Whenever the cloud was taken up from above the tabernacle, the children of Israel would go onward in all their journeys. But if the cloud was not taken up, then they did not journey till the day that it was taken up. For the cloud of the Lord was above the tabernacle by day, and fire was over it by night, in the sight of all the house of Israel, throughout all their journeys.”—Exodus 40:34-38

The cloud is both God’s Presence and His Glory. The people of Israel followed after God—they observed the signs of His Presence and Glory and followed after it.

Moses said to the Lord in Exodus 33:15, “If Your Presence does not go with us, do not bring us up from here.” We, too, must not only desire God’s Presence and Glory, we must know they are required for us to go forward—to move into the next season and go higher.

Sukkot, therefore, is a celebration that God did not allow His Presence and Glory to depart from His people as they traveled through the desert—that He led them, moved with them, and dwelt amongst them.

Today, on Sukkot, God’s Presence and Glory is celebrated and reveled in by His people—that is why Sukkot is filled with such joy. Whenever the Glory of the Lord and His Presence are truly with His people, there is little in the way of physical discomfort that can dishearten—for the joy of the Lord is our strength! The Jewish people on Sukkot look back at God’s Presence and Glory in the desert and today with hearts that are filled with rejoicing. Rejoicing that continues no matter the circumstance. No matter the weather.

They prepare for months for this season, for this stepping into the Presence and Glory of their creator as purpose and action become one.

They know the value of their God.

Symbols of Sukkot:

Unlike most Jewish holidays, Sukkot has some very specific symbols—connected to it alone. Yet, as with most other Jewish holidays, the Torah plays a vital role. Particularly in the two days following Sukkot, where the Torah reading for the past year is finished, then begun happily again.

Symbols of Sukkot

- Citron/Etrog—a lemon-shaped and colored citrus fruit

- Lulav/Palm Branch

- Hadass/Myrtle Tree Branch

- Aravah/Willow Branch

- Torah

Of these, the citron, palm, myrtle, and willow are used together as the ‘four species’ and are specifically tied to Sukkot. These ‘four species’ are often depicted in the archaeological record together—though the pieces, even separate, still hold strong connections to Sukkot. And when used together in prayer they symbolize God’s gifts of Himself and creation.

Lastly, the Torah, while not a common symbol of Sukkot, holds a unique importance—as with all Jewish holidays—for it was, and is, the Word that commanded the observance of Sukkot. Additionally, the Word brings connection to God and His blessings. It is cherished, studied, celebrated, and is a symbol—to one degree or another—of all days commanded by God.

Sukkot Symbols Found in Archaeology and History:

Sukkot symbols are perhaps the most recognizable and unique symbols of Jewish holidays found in the archaeological and historic records. For instance, the ‘four species’ can be found on coins, mosaics, and other artifacts throughout the centuries in Israel and around the world—wherever God’s people have traversed.

While sometimes found separately, the citron and other symbols of Sukkot are common and highly cherished within the Jewish community—as can be seen by their extensive use. Further, when the four are combined they are only tied directly to Sukkot. Yet, even when depicted separately, they show us the importance of Sukkot.

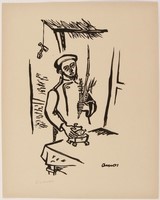

Even the Holocaust could not stop their depiction or use—though it did bring extensive challenges and danger. One beautiful example of Sukkot symbol usage during that time is that shown BELOW. This pictured lithocut from 1940, illustrated by a Jewish man, Imre Amos, who sadly perished while in the Ohrdruf, Germany concentration camp only four years later.

This lithocut depicts a Jewish man celebrating God’s commandments by reciting a prayer as he holds the ‘four species’ in his sukkah. It tells the story of a man who likely faced many trials for merely being a Jew, but still obeyed God—his faith and commitment to Him not shaken.

Through the survival of this lithocut we see that, while the Hungarian Jewish artist, Imre Amos, did not survive the ordeals of the Holocaust, his work did, and continues to show both Jew and Gentile alike the importance of Sukkot. Because Sukkot reminds us of the goodness of the Father, even as we go through desert times.

In Part TWO of this two-part series entitled, Sukkot: Follow the Cloud of God, we will continue to examine artifacts related to Sukkot. Additionally, we will see how the Jewish roots of our faith can benefit both Jew and Gentile walks with God. We will see how following the Cloud—God’s Presence and Glory—brings us not only into closer relationship with Him, but allows us to experience God’s blessings and benefits.